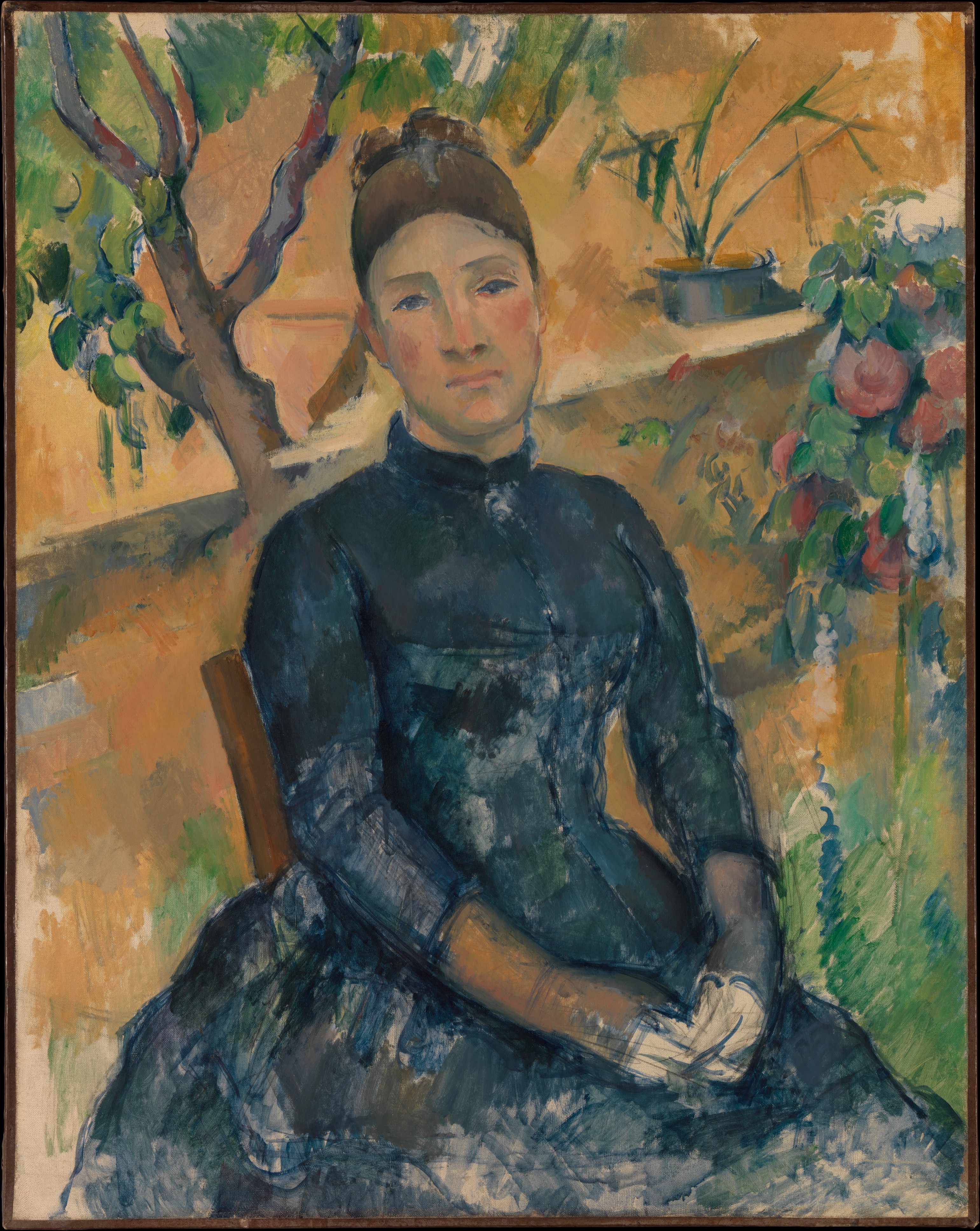

Hortense Fiquet, stares impassively. She is not strikingly beautiful, hardly, and her oval face is pale and smooth like a hard-boiled egg. You wonder what the artist saw in her face that compelled him to paint her 29 times, excluding sketchbook after sketchbook of Hortense’s pencil drawings.

She is Madame Cézanne, Paul Cézanne’s lover, wife, the mother of his only son and his most painted model. The Metropolitan Museum of the Art has put together the “Madame Cézanne” Exhibit (Nov 19, 2014 ~ Mar 15, 2015), bringing together 24 of the artist’s painting of Hortense.

Madame Cezanne in the Orchard (image credit: MET Museum)

To understand the significance of the woman behind the great man, we must first find out about the man.

Cézanne, a Post-Impressionist painter, has inspired modernist painters like Picasso. Cézanne rejected Impressionism’s emphasis on light and color, and turned to structure, order. Jackie Wullschiager wrote in a review for the Financial Times:

Cézanne’s directness — the balance, pictorial logic, simplification of natural forms to geometric essentials — laid the foundations of modern art

That “directness,” is visible even when painting Hortense. Cézanne absorbed her face, exploring the sharp angles and planes of her face, painting it over and over, and reducing it to odd geometry. The artist was not concerned with replicating her face. Instead, he ventured into early abstract art, freeing the painting from the need to represent reality.

But I wonder, had Cézanne looked at Hortense beyond a paintable object, would they be happier as a couple? The two met when Hortense was 19 year old, in 1869. Cézanne was the son of a wealthy merchant, and Hortense the daughter of a bookkeeper. She modeled on the side occasionally for extra income. Three years later, she gave birth to a son. Cézanne kept her existence a secret from his family and they did not marry until 14 years later. It was a marriage of necessity — to secure young Paul’s inheritance, not love.

Hortense was not liked by Cézanne’s family nor friends. In fact, Roger Fry, the critic who introduced Cézanne’s work to Britain, called Hortense a “sour-looking bitch.” In the Feb 25, 1952 issue of LIFE, Hortense was described as:

A volatile, talkative woman who had little interest in art and cared only for “Switzerland and lemonade.” Mme. Cézanne gradually took on a look of weary resignation during the endless sittings in which Cézanne would tell her to “be still” and not talk “nonsense.”

I can’t help but feel a little sorry for the girl. Sure, she has her faults, but Cézanne himself was far from being an ideal husband. In addition to keeping Hortense as an underground lover for 17 years, he often lived apart from Hortense and their son, and did not achieved financial success until mid-fifities.

In fashion advertising, we talk of “the gaze.” There is the person doing the looking and the person who is being looked upon. In most scenarios, the looker is empowered because he or she has the ability to transform the object as he or she sees fit. The looked upon, the object, is powerless to reject interpretations.

Cézanne, the looker, famously reduced Hortense to shapes — ovals, triangles, ellipses — 35 years before Picasso and helped introduce abstract painting. But perhaps if he did not merely see her as still life (hint: apples and oranges) or geometric shapes, he might discover that she has more than just lemonade to talk about.

(Read more about the exhibition from The Telegraph)